Dr. Byrne's Teaching Philosophy

Contextual quotes that frame my teaching philosophy:

“The mind is not a vessel to be filled but a fire to be kindled.” ~ Plutarch

“Teachers open the door. You must enter by yourself.” ~ Chinese proverb

"Tell me and I will forget; show me and I may remember; involve me and I will understand." ~ Confucius

“(Intelligence) is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration.” ~ Thomas Alva Edison

“Today a reader, tomorrow a leader.” ~ W. Fusselman

“When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it is tied to everything else in the universe.” ~ John Muir

"High-quality learning is absolutely essential to high-quality living." ~ L. Dee Fink

A. Introduction: Teaching Is About Relationships

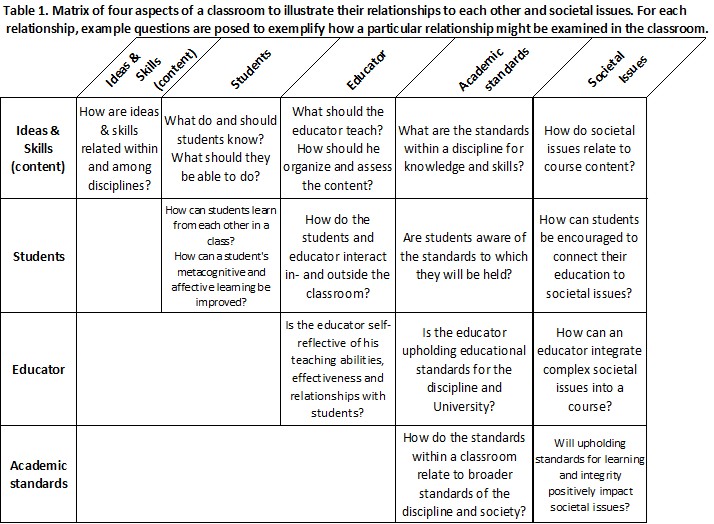

As an ecologist, I see the world in terms of relationships. This worldview naturally influences how I think about my simultaneous role as an educator. As such, the word relationships provides an appropriate broader theme for my educational philosophy. In many ways, I envision the scholarship and practice of teaching as engaging in the study and management of the “ecological relationships of the classroom.” The key relationships embodied by this educational ecology, in my view, are those among content (i.e., ideas and skills), students, the educator, and academic standards. A matrix created from these four classroom dimensions yields ten pair-wise relationships that can be examined for a given course (Table 1). In addition, an integral part of my teaching is emphasis on relationships between my classes and societal issues (e.g., pollution, biodiversity conservation, energy generation) which provide essential broader context for student learning and the goals of higher education. As such, the four classroom dimensions can further be examined in terms of their relationships with societal issues, as illustrated by the far right column of the matrix.

In the rest of this statement, I utilize this matrix (Table 1) to organize discussion of selected aspects of my educational philosophy, including pedagogical techniques. For the sake of brevity, all of the fourteen possible relationships will not be discussed explicitly and individually; however, aspects of some implicitly underlie the discussion of others, suggesting that the four dimensions and societal context can be interrelated to each other in more complex ways. Indeed, the social-intellectual complexity that characterizes a “classroom ecosystem” and the “societal landscape” that surrounds it mirrors the biophysical and spatial complexity that ecologists study in environmental ecosystems and landscapes. Thus, for me, being an ecologist and an educator provides for an exciting and stimulating career with many opportunities to think about relationships among humans, ideas, societies, biodiversity and environments, both in and outside of classrooms.

B. A Learner-Centered Approach to Classroom Relationships

Educator as facilitator of student engagement with ideas

In my view, student engagement with ideas is the most central relationship in a classroom. The educator’s connection to this is as a facilitator (or guide or coach) of student engagement with concepts (Fig. 1). (Skills development is often an essential component of student engagement with ideas; for simplicity, this will remain implicit in the text.) This perspective, which is central to my educational philosophy, is echoed in the following Chinese proverb: “Teachers open the door. You (the student) must enter by yourself.” Metaphorically, students’ passing through the door represents their engagement with ideas whereas the educator’s role of opening the door signifies the act of directing them toward learning goals, largely through designing learning experiences (inclusive of choosing readings, lecturing, asking questions, developing assignments,

creating learning activities, etc.). Although educators’ relationships to students and content are very important for catalyzing student learning, educators cannot force students to move through the learning door. Thus, I see the relationship between students and course content as the primary relationship to think about in a classroom because, as the proverb suggests, students are ultimately responsible for their own learning. Pedagogically, I emphasize this standpoint to students by placing this Chinese proverb on my syllabi (with the other quotes above) and presenting a few slides on the first day of class that summarize my teaching philosophy. As part of this presentation, I remind students that, at a fundamental biological level, learning is ultimately a process of rewiring neurons in one’s brain; unfortunately for them, I explain further, I cannot—nor can anyone else—enter their brains to fire neurons and create knowledge for them. Thus, each student must take responsibility for participating fully in his or her own individual learning process, while the educator serves as a valuable “guide on the side.”

In more academic terms, my educational philosophy embraces a learner-centered approach, which has been described magnificently by Maryellen Weimer in her book Learner-centered Teaching. I adopt this approach because it is clear to me—based on my own learning and teaching experiences and an emerging body of pedagogical research—that cultivating a learner-centered classroom provides for a more effective learning environment than the historically dominant instructor-centered teaching approach. The model for this latter approach was that of teacher-as-a-talking-expert whose knowledge could easily and directly be imparted on students, largely through lectures. In contrast, a learner-centered pedagogical model gives more responsibility to students by emphasizing their roles in internalizing content and generating their own understanding and knowledge.

In the learner-centered model, the teacher remains an important member of the classroom (especially as an assessor of student understanding in relation to academic standards) but has a role of a mentor and facilitator of student engagement with ideas rather than as solely a provider of information. Putting a learner-centered educational philosophy into practice requires the use of different teaching and assessment methods than just lecture. I incorporate these into my classes as much as possible with, I believe, successful teaching and learning results (granted, however, that some students resist becoming more active than being passive note-takers—or worse, nappers!). Elsewhere in this statement, some of these pedagogical methods are described to exemplify how I foster active, engaged relationships between students and ideas in my courses.

Learning outcomes describe student-idea relationships

Learning outcomes are a critical component of my leaner-centered educational philosophy (and thus represent the educator-content relationship of Table 1). Learning outcomes are the end results of the learning process: the information, understanding, and skills (and to some extent, attitudes) that students should have gained as a result of a learning experience (or set of experiences). In course development and lesson planning, outcomes are often expressed using the phrase “Students should be able to…” (SSBAT) (I use “should” rather than “will” because this more accurately reflects the (disappointing) reality that not all students “will” achieve the learning outcomes.) The use of this SSBAT phrase reminds me and students that, at the end of the day, their academic success is determined by their attainment of certain outcomes. Furthermore, inasmuch as outcomes should be informed by appropriate academic standards, they help define the important nexus of relationships among academic standards, students, course content (defined by the outcomes), and the educator (who prepares them).

To implement a learning outcomes approach to teaching, I adopt a “backward design” approach to developing classes (sensu Wiggins and McTighe’s book Understanding by Design), in which the structure of a course and individual class meetings are designed using the learning outcomes as guides for developing presentations, activities, and assessment methods. Adoption of this approach helps me clarify, often on a class-by-class basis, what ideas and activities I should focus on in a class period. This increased clarity, in my view, improves the intentionality of my teaching; the structure of my courses and lessons; and my ability to communicate the learning goals to students.

Because learning outcomes help delineate a critical intersection of classroom relationships, they are explicit on my syllabi and assignments, and I sometimes share lesson-specific ones with students as study guides (especially in introductory classes). In this context, a key challenge is to not provide students with didactic “information-centered” outcomes that state explicitly and exactly what they should know and be able to do; if this were the case, learning outcomes would, for the student, become nothing more than instructions for rote memorization and mindless practice. Instead, I seek to write student-centered learning outcomes that are “clues” intended to steer students toward information and skill development but that require committed engagement and effort on their part to decipher and reflect on content and generate deeper understanding (further reflecting the professor’s role as a guide). Further, outcomes can be focused on higher-level thinking and skills to convey to students the importance of more than regurgitation of information. For example, a key learning outcome that links population ecology to societal issues is “apply an understanding of factors affecting a population’s size over time to development of a management plan for an endangered or pest species.” In sum, appropriately-written learning outcomes help challenge students to be active learners by fostering critical thinking and maintaining their engagement with course content while encouraging them to synthesize ideas and apply them to the analysis of societal issues.

Assessment fits in the intersection of classroom relationships

A focus on learning outcomes helps situate assessment (and by extension, grading) within the relationships model of teaching. Assessment emphasizes students’ abilities in relation to desired outcomes rather than assessing content alone. Further, using learning outcomes enables a more intentional, critical and effective relationship between the instructor and student learning: outcomes help ensure that assessment activities and materials (e.g., exam questions, rubrics for papers) are designed by the instructor to be appropriate and fair. The outcomes provide a basis against which to evaluate whether assessment methods are aligned with the instructor’s focal outcomes.

For instructional practice, I have found this outcomes-student learning—assessment framework very helpful; for example, I when drafting and revising exams and quizzes. I often generate a list of possible topics and questions to assess student learning. I try to be creative and academically “fun”, drafting unexpected and novel scenarios and questions, especially ones that will catalyze deeper student reflection and analysis. However, when I then evaluate them against the learning outcomes, I am able to refine them further and discard ones that do no match well with what I asked students to learn and do. While some of fun questions would be great for classroom discussion, they may be too open-ended and arbitrary to properly assess student attainment of the predetermined learning outcomes. This process embodies a key part of the backward design process that helps keep the instructor-idea relationship focused and intentional. In the context of assessment, learning outcomes help me be more self-reflective about my pedagogy, which embodies the educator-educator relationship in Table 1.

A key part of my assessment philosophy and practice is the use of formative assessment methods to complement summative approaches like final papers and exams. Formative assessment techniques, such as quizzes, reading worksheets and small in-class projects, provide an intentional way to simultaneously teach, gauge student progress toward meeting outcomes, and provide students (collectively and/or individually) with feedback about their progress, especially what they still need to learn. For example, as part of an introductory lesson about the carbon cycle, students engage in an in-class group project to explore the cycle and then complete a worksheet for homework; we then review the answers and student reflections about them to start the next class. I collect the sheets (to formally award points for competing it) and am able to gain more specific insights into collective and individual student understanding. Throughout this lesson, I can clarify misconceptions and provide students with individualized feedback (during the in-class activity and discussion and on their individual worksheets) prior to summative assessment via the mid-term and final exams. In this regard, formative assessment methods become integral parts of the teaching and learning process, both helping instructors and students reflect on and improve student learning.

Formalized, intentional assessment of student learning outcomes, both formative and summative, is also a critical component of the student-student relationship in my relationships matrix (Table 1). This relationship is one of metacognition in which students are given opportunities to reflect on their thinking and learning, and evaluate their personal levels of achievement. For this to happen though, the educator must provide specific and (hopefully) immediate feedback to students about their performance on assessment activities to complete the learning—assessment—educator response—learning loop. In this context, a key part of my educational philosophy is to provide students with feedback needed for them to engage in self-reflective practice. I don’t take for granted that students will do it on their own so I often encourage them to “read my comments carefully to guide your further learning” (especially in papers). Also, I provide opportunities for students to explicitly reflect on their learning progress by asking them to write reflectively during in-class “minute papers”; for example, I ask them to state what they learned or a “muddy point” they have from the previous lesson or about a particular topic. These reflections provide me with another way to assess their learning while simultaneously giving them additional opportunity for self-reflection. Based on my experiences, the intentional use of “assessment as pedagogy” helps improve relationships between students and content, and students and themselves via enhanced metacognitive thinking.

C. Relationships among Ideas

I believe that a central objective of education should be to provide students with the foundational knowledge and skills needed to understand and discover relationships among ideas within and among disciplines. For this reason, I strongly support a liberal arts curriculum and enjoy teaching inter- and trans- disciplinary courses such as SUST 101 and Urban Ecosystems. As an ecologist, I am particularly interested in exploring interdisciplinary relationships with students by using concepts from biology and environmental science as starting points from which linkages between science and society can be discussed. In the classroom, I put this part of my educational philosophy into practice, in part, by giving presentations that incorporate a broader interdisciplinary context and asking discussion questions that guide students toward thinking about relationships among scientific knowledge, contemporary societal issues, and their individual opinions and worldviews. Although the nature and depth of the relationships to be made among ideas vary among classes, I believe that they can and should be found in courses at all educational levels and within majors’ and general education non-majors’ courses. As such, I begin designing my courses around the answer to this question: how does the content of this course relate to that of courses across the liberal arts curriculum and, for courses within the biology and environmental science majors, the content covered in other courses within these majors? (With reference to Table 1, this provides an example of how the educator relates to course ideas.) In the classroom, I share some insight about my answers to this question with students and also explicitly or indirectly ask them, through various assignments, to think about how they could answer this question. In this way, I hope to facilitate their development of the critical thinking skills needed to explore and discuss relationships among ideas and, in turn, gain inter- and trans- disciplinary knowledge.

One pedagogical method that I use to explore relationships among ideas with students is the creation and discussion of conceptual models and frameworks that help organize ideas and their relationships. Thus, one of my central teaching objectives is to organize course content around conceptual frameworks (that are interdisciplinary where appropriate) that I share and discuss with students. Throughout courses, I encourage students to create their own frameworks that reflect their personal understanding of class material. (For example, in Soil Ecology, I have students draw, in small groups, their own models on the board which we then compare and evaluate.) Such conceptual frameworks are useful for helping students integrate knowledge and see relationships among the diverse ideas within and among classes (e.g., molecules to ecosystems) and disciplines (e.g., sociology and ecology). In addition, they provide a useful assessment tool for exposing how and where students’ understanding of concepts can be improved. Conceptual models and frameworks are also useful focal points with which to spark discussion of human-environment relationships and link theory with applied problems and solutions, a crucially important skill within environmental and sustainability studies.

D. Fostering Student-Student Relationships to Deepen Relationships between Them and Ideas

Although relationships between individual students and ideas have a central place in my educational philosophy (Fig. 1), I believe that relationships among individual students are an important component of an ecologically dynamic classroom. Students surely learn from each other when they help each other engage with ideas in group activities such as discussions and solving problems. In addition, students need many opportunities to develop interpersonal communication and collaboration skills. As such, in my classes I seek to foster student-idea relationships as often as possible through the utilization of, hands-on, interactive group activities. For example, in BIO 104 three class sessions are used for a jigsaw exercise in which each student in a group has read a different journal article and then shares the “take-home message” of this paper with their group members; the group then collaborates to prepare for writing a summary paper by starting to synthesize the research from across the papers. As another example that fosters student-student interactions, I designed a role-playing food web exercise in which students take on the identity of various organisms and then have to move around the classroom to find other students whose identities they can “consume.” After these ecological links are established among students, they draw their relationships on a poster that we use to discuss the types of linkages made, the overall structure of the food web and relationships between species interactions and societal issues such as pest control (Byrne 2013).

In my experiences, students are more engaged with ideas and enjoy the classroom environment more when working in groups than they are if I was the only one talking. Because I strongly believe that allowing students to interact with each other in the classroom helps their overall learning, one of my central teaching objectives is to continually revise and develop novel teaching methods that engage students’ minds and provide them with rewarding learning experiences. In addition, when students are actively engaged with each other, a more ecologically dynamic classroom is created that is also more stimulating and enjoyable for me as an educator.

E. Idea-Student Relationships in Relation to Academic Standards

As part of my educational philosophy, I try to articulate for myself and students how course outcomes and assessment relate to academic standards both within and outside of the University. My belief is that I have a professional responsibility to challenge students to work toward reaching the highest, yet appropriately challenging, standards for a given education level. Likewise, I have become more explicit in my communication to students (especially in majors’ courses) that their performance will be assessed in the context of professional academic standards for a given discipline (which help guide the articulation of outcomes). For example, in the laboratory section of BIO 104, I repeatedly emphasize the need for students to use proper reference list formatting and make professional looking figures for their laboratory reports and then assessed these aspects of their finished projects against the standards. (In my role as BIO 104 lab coordinator, I made posters to illustrate these standards that are displayed permanently in the lab room (except during quizzes!.) In practice of course, I do not expect students to be able to perform as well as seasoned professionals for many outcomes; however, by explicitly establishing a relationship between academic standards and my expectations for student learning, I hope to convey to students that the professional world outside the classroom will also expect them to achieve certain outcomes and that their success will depend on their relative ability to meet, and preferably, exceed normalized expectations.

Also regarding academic standards, I utilize pedagogical methods in my classes that relate to the expected student learning outcomes of my department, the University and broader society. In my science majors’ classes for example, I am committed to helping students improve their scientific thinking and research skills by providing them with opportunities to conduct library and laboratory research where possible on topics of the students’ choosing. These activities are related to professional academic standards because all students completing a biology or environmental science major should be able to design experiments, collect reliable data and conduct scholarly research in peer-reviewed scientific journals. In addition to gaining relevant skills, I believe that providing students with such learning experiences helps cultivate greater enthusiasm for learning and research among them while giving them senses of ownership and accomplishment that increase their confidence and desire to conduct further research. I have seen such attitudes develop in many of the students I have worked with (both within and outside of classes) after they completed semester-long research projects. Encouraging students to think about how they would develop and execute such projects and, when possible, actually gather data and present it in posters, reports or talks are central components of my educational philosophy.

Maintaining high academic standards related directly to my deeply-held personal conviction that possessing high-quality skills for building effective relationships among words (i.e., communication and especially writing) is vital to success in every discipline and career. This influences my educational philosophy and teaching practice in that I assign many writing projects (formal and informal, large and small) in all of my classes and provide students with detailed feedback about their writing. From my experiences with undergraduates, I am concerned that writing is becoming a lost art form and that too many students lack appreciation for basic grammar, spelling, and writing style (perhaps because of technological influences such as email). However, as I tell all of my students, it doesn’t matter how much one knows if one cannot clearly communicate that knowledge to others by building effective relationships among words. As such, I believe that it is my responsibility to uphold the highest academic standards for writing in my classes to help communicate to students about the broader societal expectations and standards for appropriate and effective writing. To this end, I provide students with opportunities to improve their skills through multiple small and large writing assignments in each class. (For example, in BIO 104 students are assigned two small review papers; the second one is worth more points toward the final grade, thus giving them an opportunity to improve that has more impact on their grade.) On their first papers, I provide substantial and detailed feedback to they can learn and improve on the next paper. Although this is labor intensive for the instructor, students need such chances to improve their writing skills, and my philosophical perspective about the importance of writing “forces” me to commit to doing my part by providing those opportunities in all my courses. That my conviction about the importance of writing is valuable has been communicated to me over the years by comments received from alumni. For example, one former student told me that he greatly appreciated my emphasis on writing quality because it made him a better writer in his law school classes. Such feedback increases my confidence in communicating to students that my commitment to high expectations for writing is important for helping them prepare for future careers and projects.

F. Relationships between Students and the Educator

Student-educator relationships, independent of content, are also critical to consider as part of any thorough educational philosophy. My personal love of learning has been cultivated by many of my teachers who have challenged, inspired and befriended me. In turn, teaching provides me with great personal satisfaction as I watch others learn and express enjoyment in thinking about the diversity of relationships in the world. In particular, I enjoy developing one-on-one classroom relationships with individual students as I help them organize knowledge and develop deeper understanding and appreciation about the complexity of relationships. However, I have come to accept that not all students will be receptive to my efforts to facilitate their engagement with ideas and their own learning (i.e., the nature of the relationships shown in Fig. 1 fails to materialize for some students—perhaps because they just want to be “told what I need to know”). Nonetheless, it is central to my educational philosophy—and personality more generally—to strive to cultivate respectful relationships with all my students regardless of their level of engagement in a course. No matter a student’s disposition, I will continually strive to inspire students to think about, appreciate and, for some, further engage in the study of relationships among ideas. Indeed, I am fortunate to have a career that provides me with the opportunity to participate in one of the greatest possible relationships between people: a career in which opening a door for someone leads to one of the best possible outcomes an individual can achieve—a learner-centered, high-quality education.

G. “What is education for?” and Students’ Personal Relationships with the World

A key component of my educational philosophy is considering of the role of higher education in relationship to societal issues, especially those relating to “big questions” facing humanity such as how to create sustainable social and ecological systems (the right-most column in Table 1 above). The environmental-education scholar and critic David Orr has framed this topic in the form of the question “What is education for?” In one of several essays about this, he concludes:

More of the same kind of education will only compound our problems. This is not an argument for ignorance but rather a statement that the worth of education must now be measured against the standards of decency and human survival—the issues now looming so large before us in the twenty-first century. It is not education, but education of a certain kind, that will save us.

He goes on to suggest that the certain kind of education needed involves 1) basic knowledge of ecology and human-environment relationships, 2) “mastery of one’s person,” and 3) an appreciation that with education comes a responsibility to use knowledge well. In a very personal way, I agree wholeheartedly with Orr’s arguments: education is “for” helping students become citizens who understand their relationships to the environment. More specifically, as an ecologist I especially agree that all students—not just biology and environmental science majors—should have to learn basic ecological information especially as related to humanity’s reliance and impact on biodiversity and ecosystems. Given that these are generally accepted topics to teach to students, these components of Orr’s certain kind of education are easy to understand and accept.

However, the latter two issues seem—to me at least—to be less easily integrated into one’s classroom. How does an educator effectively engage students to think about the “mastery of one’s person” (especially what that really means)? Is it appropriate for educators to pepper lessons with discussions of what constitutes responsible use of knowledge by students? Perhaps my slight discomfort with these questions—despite my personal embrace of Orr’s argument that they should be part of contemporary education—derives from my disciplinary background as a scientist: these affective issues that relate to ethics, values, and subjective personal decision-making fall outside the realm of traditional scientific education. Increasingly however, I reject this notion and fully believe that educators have a responsibility to explore the more personal dimensions (including emotional connections, opinions, value-driven behavioral choices) of topics and human existence with students, even in traditional basic science classes. Doing so helps place the content and students’ learning within a broader context that includes self-reflection and societal issues, essential parts of engaging students in deeper “significant learning experiences” (sensu Dee Fink’s philosophy as explained in the book of the same name).

As part of my educational philosophy, I seek to help students achieve more significant learning by helping them develop their own personal relationships with content and controversial societal issues, providing opportunities for self-reflective practice, and then guiding them toward articulating their own opinions, values and personal actions related to those issues. This is tricky work and may make some educators uncomfortable. However, as my philosophical stance on this topic has become clearer and stronger, I have resolved my own discomfort by adopting pedagogical approaches that facilitate broaching affective and controversial issues in classes.

First, I communicate to students the importance of considering the affective and societal dimensions of course content. Discussing them helps us learn about others’ diverse views and improve our skills for engaging in civil discourse; it helps us become more engaged and functioning citizens in a community. Further, I communicate to students that, for many issues, there is not right or wrong view per se, so they should feel comfortable expressing their personal beliefs and experiences. I try to create open, welcoming classroom environments in which students understand the value and relevance of expressing their personal views, and they understand that their views will be respected even when others disagree with them. To this end, I adopt a bumper sticker that hung in my eighth grade civics class into my educational philosophy: “We have a right to disagree but we should not be disagreeable.”

Within this context, I provide time for and encourage classroom discussions as much as possible. I use Socratic questioning as a central pedagogical strategy; beyond basic content, this naturally leads to me repeatedly asking students, “What do you think about this?” or “What would you do in this situation?” I have developed a few formal lessons and activities that are meant to draw out students’ opinions and spark debate. For example, in my published case study about lawn and garden ecology—which I have used in SUST 101 and Urban Ecosystems—I ask students to articulate their ethical views about complex social-environmental problems associated with fertilizer use and pollution, biodiversity loss and other urban issues. This has always led to wonderful and engaging roundtable discussions that help students understand that societal issues are not always “black and white.”

Another strategy I use for exploring controversial and affective topics with students is to introduce examples of arguments for certain ethical positions or behaviors. For instance, I use phrasing in the classroom such as, “Some people believe this or do this because of this…” or “If you wanted to reduce your carbon footprint, you could do this…” or “Those who care about protecting elephants can do this….” This language provides information and suggestions rather than demands (“You must believe or do this…”) and, avoids making judgments (i.e., the statements say nothing about how “holier than thou” people who believe or do the things are). In my experience, this approach has enabled me to introduce topics while avoiding strong student pushback. (Rather, I think that most students are excited to hear about what they can do to make positive differences in the world.)

To ensure that all students are reflecting on issues—even those not participating in discussions—I often ask students to write about their reflections. This is done in formal paper assignments and with informal, in-class “minute papers” (i.e., few sentence responses to a question; what I call “half-sheets” because they are done on half-sheets of reused paper). The in-class writing is required to earn credit for attendance, which is a part of the final grade. However, the responses on these are not scored or judged on any basis of right or wrong; as long as a student writes something relevant they will receive the full score for that activity. Likewise, for the formal essays, students are not assessed based on the specific points they make (they are scored, however, on the English mechanics and overall success of their argument). The goal of these assignments is for students to engage in personal critical thinking to explore their own values, beliefs and opinions in the context of class content, which they may not otherwise do. Sometimes I do comment on their personal views as appropriate to encourage them to make additional connections or reflections or clarify their points. In my view, the key to making these assignments successful—such that students are comfortable with providing honest answers—is to make it clear that, in the context of such topics, the learning outcome is not whether they agree or disagree with my or others’ comments and views; rather, the significant learning occurs when they are able to respond by clearly articulating their own views and values, explain what influences them, and describe what responsibilities they think they have with respect to the knowledge they are gaining.

To the extent humanly possible, I make all efforts to avoid allowing my personal biases and views to enter the classroom so that I am not the focus of the discussion and students don’t feel compelled to agree with a view just because it’s the instructors. This is inherently challenging, especially with environmental topics for which it is usually and obviously implicit what the common scientific view is (e.g., climate change and biodiversity loss are bad) or the framing of lessons reveals an inherent bias. Of course, I sometimes reveal my personal views but, to the degree that it happens, it may have the positive effect of “humanizing” me and making me a critical part of the classroom community. Even with some risk that I may divulge my personal values and views and alienate or offend some students, my philosophical perspective about the value and need to engage students in the personal dimensions of issues (especially controversial societal ones) compels me to integrate them into the classroom. The desired outcome of this—catalyzing deeper significant learning among students and helping them “master one’s person” in the words of David Orr—is simply too important to not do so.

H. Conclusion

In conclusion, it seems that I have no choice but to help students explore the relationships arising between their own values and ideas, and societal issues. In the long run, these relationships— including students’ connections to their metacognitive practice, and those among disciplinary knowledge and society—are perhaps the most important ones that educators can help students think about. Ultimately, helping students achieve these broader significant learning outcomes reflects, in a more meaningful way, how I seek to put my educational philosophy of creating ecologically dynamic, learner-centered classrooms into practice. It is my sincere hope that my philosophy and practices help students positively affect society, other species, the biosphere and, of course, the students’ personal lives. In the end, my education philosophy builds naturally toward responding to the larger question—the question that perhaps all education philosophy statements should address in some way—“what is education for?” In my view, education is for helping us better understand the myriad relationships in the world so that we can understand it better and interact with other in it with greater clarity, purpose and positive outcomes. My role as an educator, then, is to create the most “ecologically dynamic” classrooms that I can to better enable students to meet this big-picture learning outcome.